sarah kim & Dante moore

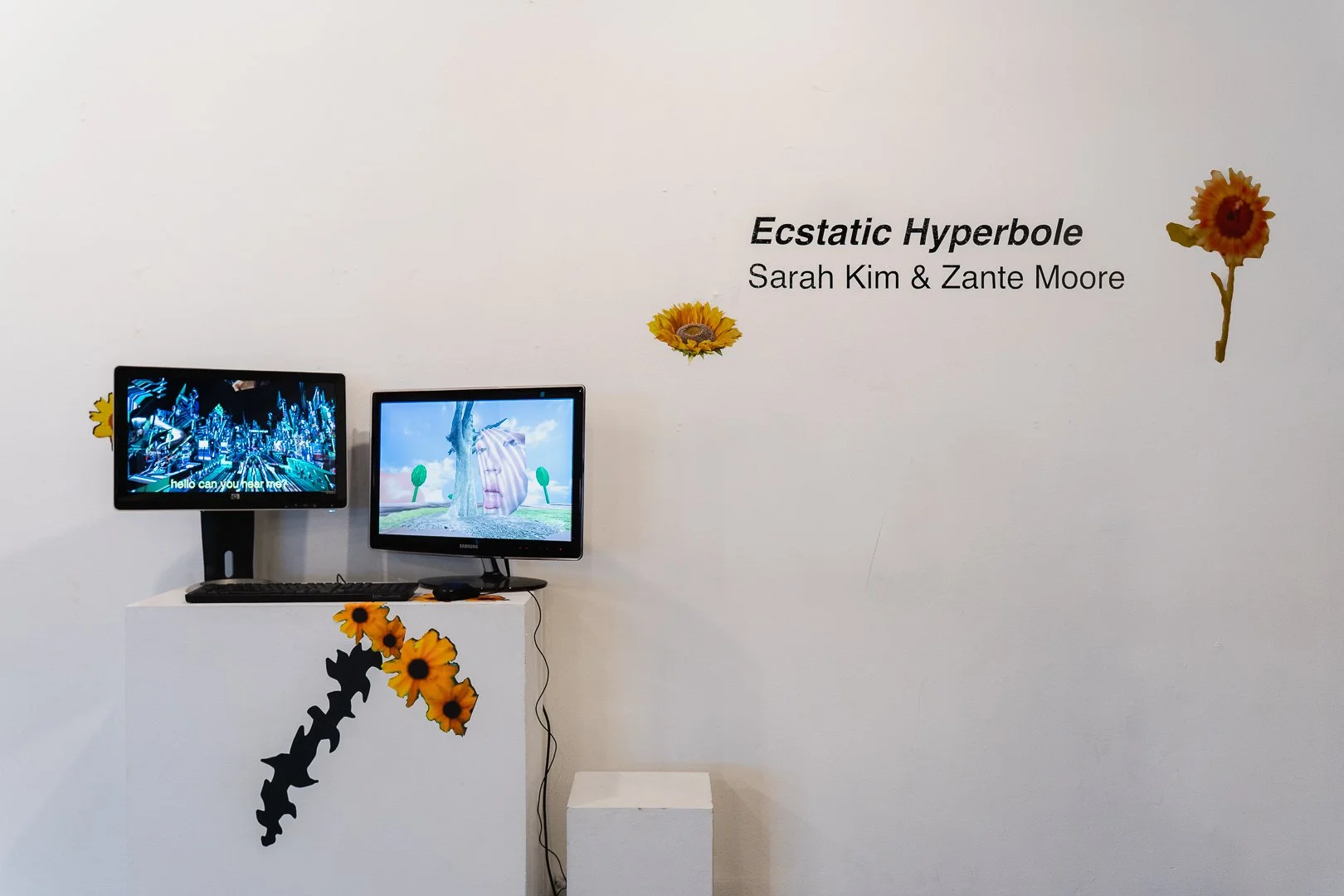

Ecstatic Hyperbole

july 2025 - september 2025

sarah kim & Dante moore

Ecstatic Hyperbole

Artist Bios:

Sarah Kim is a multimedia artist and cultural producer from Alabama working in Chicago, IL, where she received her BFA (2022) from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her practice employs a range of technological mediums to construct personal narratives that engage with and subvert dominant media tropes. In parallel with her studio work, Sarah operates as a cultural producer within the fields of art and technology. She has contributed to the development and realization of contemporary media art programming through her roles in production and curation at CURRENTS New Media and ArtificeNYC. Her work in these contexts centers on facilitating artist-driven initiatives and fostering public engagement with emerging forms of artistic practice.

Zante Moore (b. 2000) is a post-internet artist originally from Tulsa, Oklahoma. Their work blends photography, sculpture, and video games to explore identity and internet culture. Moore creates immersive installations using memes, digital imagery, and personal photos. Influenced by internet theory, their work reimagines self-image in online spaces.

Interview

Yeeseon Chae: I'm curious about what kinds of texture or qualities you like to draw out in both your physical and digital work. Because I feel like digital art tends to be described as both flat and multi dimensional, and I love thinking about that tension.

Sarah Kim: In terms of the physicality of this medium, I know exactly how I was attracted to it. Spending time on software like Maya 3D, you can get a preview of your animation through this thing called Playblast, which shows all these measurements and the wire frame behind it, so there’s so much rich texture behind the software that is technically provided. Some of my works are from 2020 and 2021, and I love seeing the texture of technological artifacts change over time, and seeing even my old works as artifacts. Textures of time, textures of meshes being fucked up, when now it's probably really pristine and perfect. I also love looking through file folders, making sure to organize them in certain ways. Even that is a texture of 3D artists, and working with those folders, you're constantly reminded of the beauty of file management, naming your file names things like “second iteration.”

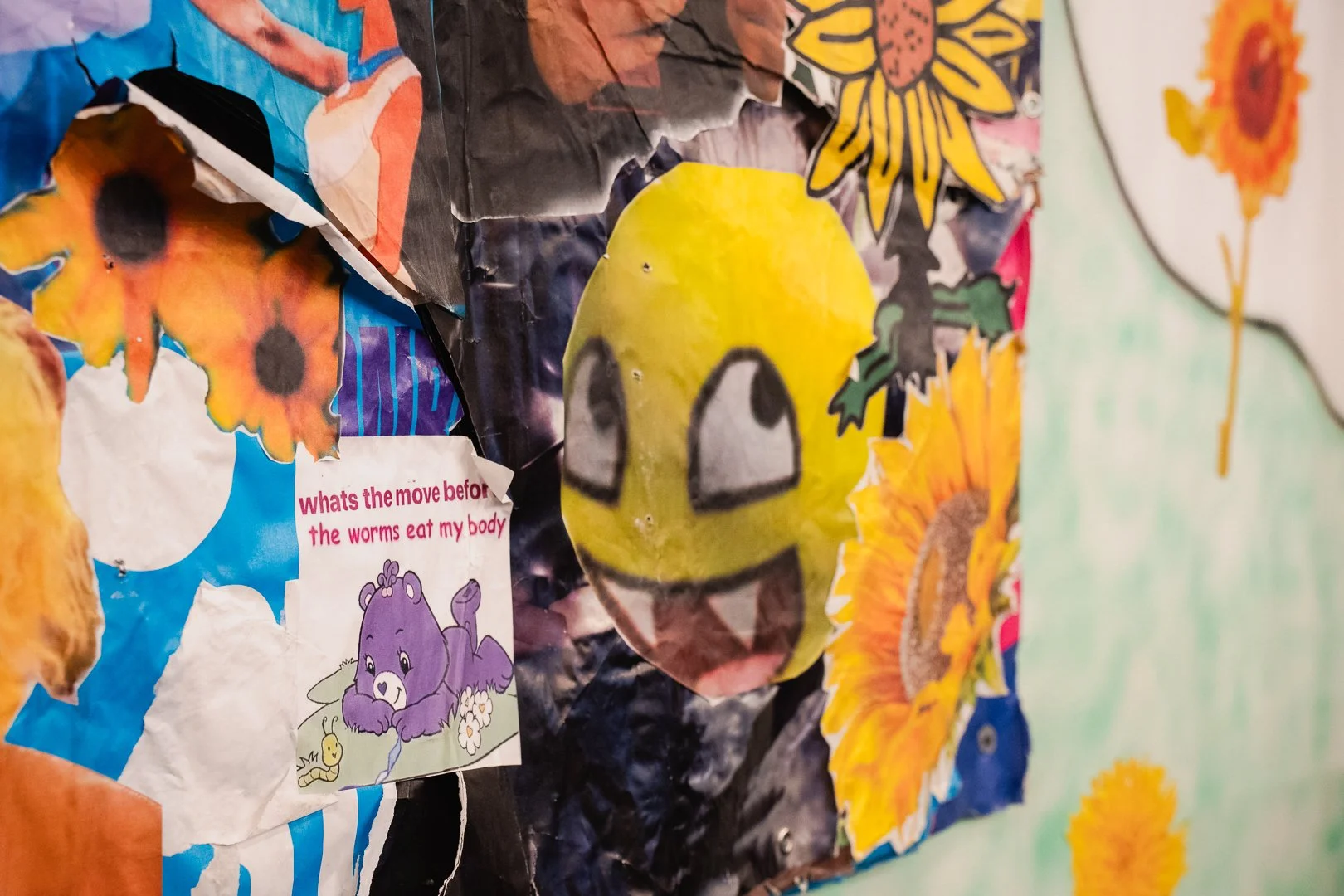

Dante Moore: I'm really interested in what you said about the texture of time too. These sorts of wallpapers I make with old images I've collected show a texture of time, and there’s this term from an article by Hito Steyerl that I really like: the “poor image.” I think memes in general and JPEGs are always sort of artifacting because they're getting screenshot reposted. And like, when a meme is super deep fried, you can see the evidence of time in it. I think that totally shows up in these wallpapers I make. One thing I try to do when I print, specifically, is to print on cheaper bond paper so that it’s flat and thin. I try to have the paper match the deterioration of the memes that I’m putting on. One thing I think about with my practice, and maybe this is a little bit of a tangent, but I do like this idea of working with something that's sort of considered “low brow” culture. I think in art, you have to be careful to not try to capitalize on it, or elevate it to a point that it's not the original message. So I think about this idea of the poor image, this idea that that you can immediately tell how old these images are, that they're from the 2010 meme era or something. That’s one thing about technology: there's this sort of fear that you can get left behind, because it's always moving so fast. And I think that has to do with the texture of time too, this idea that technology is always the next best thing.

Yeeseon Chae: Yeah, I feel like we were talking about it earlier, but I wanted to ask about how parody and play come into your works. Now that we’re talking about the line between low brow as parody versus elevating it beyond its original context and meaning: When do you feel like you have enough permission to be able to talk about something? I also want to know specifically how parody and play factors into your work, and how your personal internet practice, or personal technology practice, appears in it. Is it more difficult to be playful online now versus when you were growing up?

Sarah Kim: I think I’m parodied out. I feel like I don't know. I had to grapple with a lot of the mental and emotional dissonance in what a parody actually means. It made me feel disconnected, and I had to ask, where’s the line with parody. I still haven’t figured it out. I think when it comes to like, parody and play, it's really interesting, because using these mediums, you’re wanting to grab attention. And it's sort of an attention that I don't feel like I want to keep pleasing anymore. For the past couple of years, I've been working as a marketer, and it's not for play, it's for capital. It's intentional attention grabbing and uses these very predatory ways to gain something. I've made works in the past of how the internet has changed into these conglomerates, grabbing your data, but now I'm doing the same. So in terms of parody and play, I don't know where the line is, and I'm still on the quest of trying to figure that out. And, yeah, I'm just simply tired of it.

Dante Moore: That’s so real. I feel like, to make work about these very digital experiences, you sort of have to consume a lot to fully understand it. And I think that can get in your head because, especially as artists, a lot of the stuff you’re making is artwork, and it’s saying something, but it’s also a part of you at the end of the day. And it's this weird thing of like, having a part of you be connected to something that’s everything, which can be sad or weird. In terms of my relationship with parody and play, I think it’s funny. Doing the research that I've done for my body of work, I’ve found myself trying to be a little more bold, or more of a provocateur in my art practice. But then, in terms of my internet consumption, I've actually been trying to dial down a little bit. I don't go on social media less, or something like that, but it's literally—and one thing, too, that I'm interested in, is this idea of the over consumption of image culture and memes—it's gotten to the point to where, if I see something that’s problematic on social media, instead of just letting it desensitize me or something, I'll literally report it right away and scroll past it and block the sender. Or like, I'll try to find meme accounts or blog accounts that I feel like are doing really weird, niche, cooler things. Because of this weird dullness, this overconsumption, I've been trying to challenge my brain a little bit to get more creative with how I do indulge in the internet, in terms of when I'm trying to get inspiration for work and art. And I think a part of it, too, is about reading theory about it makes the internet the way it is. When you read internet theory, and then you see it in practice online, it makes you more cognizant of it. It’s a little bit of media literacy, in a weird way. You know how old people on Facebook will see an AI video of something, and they’re like, I can’t believe aliens are getting cows or some shit. And you’re just like, What the fuck?

Sarah Kim: Being more intentional, do you feel like it's been less fun to be on the internet and these social networks?

Dante Moore: No, honestly, I don't think it has. If anything, and maybe this is me being crazy, I feel like my algorithms been responding to me trying to be more intentional, and I feel like I've been—

Sarah Kim: —the algorithm’s speaking back to you—

Dante Moore: —yeah, the algorithm is speaking back to me. If anything, it’s sort of helped me not feel dulled down or desensitized to shit that people are bold to put out online, or get lost in the swamp of everything. Yeah.

Sarah Kim: I’m curious, if you’re collecting so many memes, are you always trying to get the best niche memes, or whatever that means? I’m curious about how you’re collecting them as you’re looking at it now, not as your sixteen-year-old self just screenshotting into folders.

Dante Moore: Totally. I think, honestly, I've been trying to not find the coolest, most niche memes, because I feel like it’s something where, if you seek it out, it won’t come to you. I think my approach now is, instead of seeking it out, I try to sit back and let stuff present itself to me in a weird way. Lately, my go-to reaction has been, when I want really, really good memes, I'll go to comment sections a lot on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, those social media platforms that let you put images in the comment sections. Those are the best ones, because people put the craziest shit.

Yeeseon Chae: I know we’re getting close to time, but for my last question, I did want to ask about AI and the use of computer generated work. Specifically, there’s this real shift towards having artificially generated things signify something that’s better than human hands, as if an AI program knows as much as an expert in any given field. Or, this question: Can artificially generated art make something as smooth and technically proficient as a painter would? I’m curious about how the conversation around AI has affected your work, if at all. Going back to how there’s a specific texture to digital work, I was watching [Sarah’s] deep fake video, and there’s so much movement, even in the face of, you know, a superimposed image. And I remember, maybe five, six years ago, there was a filter on Snapchat that you could use that would just superimpose someone else’s face onto your face. There was an uncanny quality, but you could also kind of laugh at it, because it was so obviously not you. But now that distance between knowing what is real and what is fake is getting slimmer.

Sarah Kim: Yeah, I gotta think about this.

Dante Moore: One thing I've been noticing that’s a big ass pet peeve of mine is that the meme culture has shifted. Usually meme cultures—it's like weird drawings, screenshots from real TV shows, cartoons, digital stuff—that was what I grew up to know as a meme. But now, meme culture is all—I mean, there’s a term for it, “AI slop”—you see so many AI generated memes now, and I think, all those issues I was sort of talking about earlier, I think they get heightened when AI becomes involved. I don’t know if you guys have seen the AI clap back videos on Tiktok, but they’re super minstrel-like, in a weird way. Like, it’ll be old white ladies arguing with black women, and it’s all AI. One thing that I really don’t fuck with is the AI slop memes. I feel like they’re taking over, and I feel like a lot of them are tactless. I will say, I have seen some funny AI memes. Like, sometimes they are funny, when it’s a cat and it goes to being on top of a tree with a coconut, or some random shit that you didn’t expect. But I think it heightens the speed at which people can be really stupid and problematic. And at the same time, it’s like, destroying the planet, so it’s making power bills go up. That shit’s all-consuming.

Sarah Kim: Yeah, I’m interested in what you said about humor and AI. I didn’t know there was a term for “AI slop.” This idea that AI could be funny—I mean, humor and funniness is so intelligent. It’s something of the human species. How does AI replicate this? What are they basing it off of? What’s interesting is seeing AI content generated from biases, or from typical data that has been over-massed for it to be generated. It’s like a loop of, what is it really saying about us, and what are the repetitive things that we portray online or in our behavior. I also follow the discourse of AI taking from artists, when there is a fine line of validity to remix culture or arts, which involves replicating and repeating and using other people’s creativity. There’s a lineage there in the music scene. So when it comes to the originality of an artist, I enjoy that it is an all-encompassing question for different types of arts.

Yeeseon Chae: Yeah, I wanted to ask, because there’s so much conversation about AI’s impact on the environment, and I feel very strongly about that. But in terms of it as a tool, or even like in the 2010s when it was just like—

Dante Moore: —like, Dall-E and Crayon—

Yeeseon Chae: —yeah, it would be so specific, and now it’s becoming, as you said, all-encompassing.

Dante Moore: I think with AI, it sort of reminds me of the invention of the camera. Because when the camera first came out, everyone was like, fuck the camera. That is not art. Like, if you were a photographer, fuck you. All the painters were like, Fuck cameras. I don’t think it’s completely the same, but I can sort of see that being the treatment towards AI a bit right now. At the same time, I think it’s trickier than that. I think it comes down to context and tact, and how people are using it.

Sarah Kim: I also think it's interesting how people check each other for how okay we are with AI. That’s another kind of policing that we are doing to each other, maybe as artists, or as a typical consumer, or as a friend, as family. I think that’s what’s interesting—how we permeate the topic of AI in social settings. Like, what kind of person does that mean for you?

Yeeseon Chae: Totally. There’s probably a Walter Benjamin quote that would solve all of this. Probably because it’s a tool of capital now, not in the masses. In any case, I wanted to end by asking both of you what your favorite meme is.

Sarah Kim: Now that we’re talking about AI videos, I do like the cat AI videos. Like, the MeowMeow ones with extreme relationship problems. Cats that are like, cheating on a gorilla or something, and then it'll be like, “in the living room after you’re crying.” I love those, they're so entertaining. I watch them till the end. Meme expert over here, what’s your favorite?

Dante Moore: That’s a hard question to think about. I feel like, in terms of format, my heart will always love deep-fried top text, bottom text memes. Those ones are really good. But most of the humor I get now is mostly from TikTok sound bites, like the different audios that will be popular for videos—

Yeeseon Chae: —yeah, why do they become so popular—

Dante Moore: —there’s this one Stunna Girl song, and it’s just her going, “go get anybody, we knock anybody down.” And then, they’ll put old photos of, like, 2010 Disney stars to it, and it’s just this weird, out-of-context—I’m gonna try to find one to show you guys, not for the interview—let me see. [checks phone] I always think it’s just a little farther back in my likes, and then I realized how much I consumed.

All gallery photos by Ricardo Adame

Related programming

Opening Reception:

July 27, 2025

Closing Reception:

September 19, 2025